Women, Life, Freedom: The Unsettling Power of The Iranian Women-led Politics of Resistance

A massive wave of demonstrations, following the death of Masha (Zhina) Amini, has spread across Iran since September 2022. Notwithstanding the regime’s brutal repression, the mainly women-led protest unexpectedly still persists in the country, and is echoed by large swathes of the Iranian society. The lasting mobilisation shows how women can act as the de facto leaders of the nation’s anti-government movement.

The Facts

On Sept. 16, Mahsa (Zhina) Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman, died in Tehran while in the custody of Iran’s morality police and a massive wave of demonstrations has spread across the country since that monent. Because they started with anger over the enforcement of the hijab, they represent the hardest menace the theocratic regime has faced since the 1979 revolution. These mainly women-led protests, which could persist for long time, would have been previously unthinkable in Iran, one of the world’s worst ranked countries for gender equality, for decades been ruled under the iron fist of its Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. While Iranian women have a long history of political activism and mobilisation in the country, they rarely feature at the centre of those movements. Today, Iranian women are not only at the forefront of the ongoing protests, but they are also behind its central demand, that is, the collapse of the regime. For Iran, the centrality of women in the ongoing protests was not a matter of design so much as a consequence of circumstance. Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, women’s rights in the country have been continuously jeopardized especially, but not solely, through the imposition of strict dress code rules, including compulsory hijabs for women in public. While the Islamic Republic has witnessed larger demonstrations such as the Green Movement of 2009, in which millions of protesters denounced state-sponsored vote rigging, it has never been traversed by a movement as seemingly widespread or as demographically diverse as this one. The ongoing protests have spread to as many as 138 cities, including areas once considered regime strongholds. And while the protests continue to center on the rights and demands of women, their calls for change are being echoed by larger swathes of the Iranian society, including university students, workers’ unions, and ethnic minority groups. Although there are other grievances at play such as harsh social restrictions, a collapsing economy, and widespread repression, the protesters’ opposition to the regime is shared. On February 5, Iranian pop singer and songwriter Shervin Hajipour, won the inaugural best song for social change special merit award for Baraye which is ‘For’ in English. It begins with: “For dancing in the streets,” “for the fear we feel when we kiss.” The lyrics list reasons young Iranians have posted on Twitter for why they had protested against Iran’s ruling theocracy and “Baraye” has been depicted as a powerful and poetic call for freedom and women’s rights that continues to resonate across the world.

Women’s Politics of Resistance

This is one of the first times in Iran’s history that men also join in the call for rights. They are seeing that women’s interests and their demands for gender equality and non-gender discrimination falls in line with the larger pro-democratic, pro-human rights demands that the whole society has. This renders the protest much more intersectional than ever. Therefore, the centrality of women in these protests matters for reasons that go beyond their representation or demand for equality: it falls within the paradigm of what the scholars of war and peace studies name women’s politics of resistance. More in general, a women’s politics of resistance is traditionally identified by three characteristics: its participants are women, they explicitly invoke their cultural symbols of femininity, and their purpose is to resist certain practices or policies of their governors. Women, who typically act out of social locations connected to their sex, in a politics of resistance tend to gather exclusively among them. Women “riot” for bread, women picket against alcohol, women form peace camps outside missile bases, women protect their schools from government interference, or sit in against nuclear testing. Yet, the point of women’s politics is not to claim independence from men but, positively, to organise as women. Whatever the reasons of their separatism, their organising, directing, and enacting a politics enables them to exploit their cultural symbols of femininity. Women can also organise together without relying upon common understandings of femininity: feminist actions, for instance, are often organised by women who explicitly reject the roles, tasks, and attitudes expected of them as “women”. But in a women’s politics of resistance, women rather affirm roles and obligations traditionally assigned to women and call on the community to respect them. A women’s politics of resistance is rather composed of women who take responsibilities for their tasks of caring labour and then find themselves confronted with policies or actions that interfere with their right or capacity to do their work. Hence they resist in the name of womanly duties that they have taken and that their communities expect of them.

Novel Expressions of Gendered Citizenship

The act of protesting a particular war or certain governement’s policies is a distinctly vexed activity of citizenship for citizens of any gender: protest interprets an engaged critique or resistance, rather than the reliable, disciplined, patriotic performance of prescribed responsibilities. At a time when the performance of these responsibilities is regarded as paramount, the speaker’s sacrifice demonstrates the performance of a burdensome civic obligation, but it also displays that the protester has acquired sufficient knowledge about the laws imposed by the government to speak with an authority comparable to that of the government. In their unfamiliarity, these women’s movements may prove genuinely unsettling, «but they enlarge the range of representations from which women draw in performing their roles as citizens, and in the long run, they have the potential to expand the narrow conceptual spaces to which women’s political participation has been confined» (Kathryn Abrams, “Women and Antiwar Protest: Rearticulating Gender and Citizenship“. BUL Rev. 87 2007: 849-880). In embracing this new role, the Iranian women are making a claim, not only for themselves in particular, but for the entire polity. Their protesting within movements enforces a demand for governmental accountability to the nation as a whole, rather than a demand for inclusion on their own behalf. Demands for accountability are not unfamiliar in protest movements, but they have been far less typical in movements led by women. The Iranian women and people’s outrageousness of the demand that the government stop its restrictions challenges the state to explain its actions and motivate its continuation. This choice seems paramount in the way it suggests that women can see themselves as sufficiently included to make demands of another kind, and can grasp the universalising dimensions of their own political efforts. Finally, it is worth noting that the Iranian women-led movement has acquired some valuable forms of success. First, it has claimed the attention of a media-saturated public, and even if it has not succeeded yet in stopping the government’s brutality, it has strongly contributed to a sensible escalation of protest and to its international resonance. Second, it has countered the public with novel images of gender citizenship, and only in rare cases it has been effectively shut off by the officials’ repression. Third, it has affirmed the ability of women to engage in strongly visible confrontation with governmental actors at the highest level, to start innovative strategies of direct-action protest or civil disobedience, and to act, even if temporarily, as the de facto leaders of the nation’s anti-government movement. Though they may be contested and their effects may be weak, these are no small achievements. The Iranian protesters reflect and create a larger repertoire of roles for women as they engage in more ambitious political contexts.

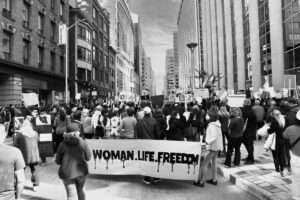

Photos: Iran Protests by Taymaz Valley

![]()