Dissent in U.S. History: Interview with Ralph Young

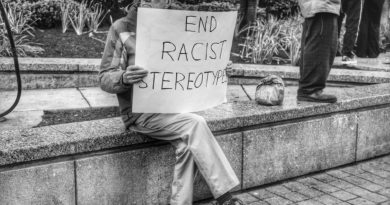

The recent events that occurred in the United States show that history is not just a matter of the past. Racism, white supremacy, gender discrimination, unlawful employment, and unjust immigration policies have shaped the history of the United States since its founding. In this context of turmoil and protests, dissent had become a powerful means to achieve America’s broken promise that “all men are created equal.”

Dissent is the defining character of the history of the United States.

It became the engine of many movements that made the history of this nation: American Indians, women, immigrants, students, the working class, African-American, LGBTQ community, and many others.

It is impossible to conceive American history without acknowledging the vital importance of dissent.

The question that America has to face immediately is what kind of nation it wants to be. Is the United States finally ready to end the unresolved issues of its past?

Professor of History at Temple University Ralph Young, author of Dissent in America: The Voices That Shaped a Nation (2006) and Dissent: The History of an American Idea (2015), states in the introduction to his 2015 book:

Dissent created this nation, and it played, indeed still plays, a fundamental role in fomenting change and pushing the nation in sometimes-unexpected directions.

I found his words extremely inspiring.

The more I read them the more something I had buried a long time ago in myself resurfaced. It was the power of dissent in people’s life and history. Astonishing.

I had the privilege of interviewing Ralph Young some days ago. I had an Epiphany.

Here you find an abridged version in English of the full interview available in Italian in InStoria.

The United States is a product of dissent. Even before the United States was formed the first English colonies were founded by religious dissenters—Puritans, Quakers—and by the end of the seventeenth century significant political dissent arose that eventually led to the American Revolution […] Dissent was so central to the American character that the right to dissent was put into the First Amendment to the Constitution and Americans have dissented ever since […] It is clear that dissent is one of the defining characteristics of what it is to be an American. It is central to our beliefs. It is in our DNA.

How did dissent evolve over the centuries by affecting activism and grassroots movements? Is there a correlation with the notion of injustice in American history?

What is the relation between dissent and American culture? Can you provide some anecdotes relating to Pete Seeger and Allen Ginsberg, specifically how they changed your life (if it is possible to know) and why the contemporary generation should take inspiration from them?

So whenever I’ve been in despair about the state of the world, or my own life, I often harken back to those times when I met these two creative, inspiring men. Both, though so different from each other, were totally approachable and not at all full of the ego that usually dominates celebrities’ personalities. In talking with Seeger and Ginsberg I felt I was talking with an old friend.

In your opinion, how do dissent and technological progress relate to each other? How are the new media affecting the original notion of dissent and activism?

Dissenters have always used the latest technology to get out their dissenting message more broadly. The latest technology at the time of the Protestant Reformation was the Gutenberg Press. This enabled pamphlets and translations of the Bible to be distributed throughout Europe. The Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s became more widespread because of television coverage of the demonstrations. Civil Rights and antiwar songs got a wide audience because of improvements in high fidelity, stereo, recordings of albums, and proliferation of radio stations. So dissenters have always found use for the latest technology. Today, with the Internet and social media, Facebook and YouTube, smartphones, video recorders…. dissenters can get word out of when and where the next demonstration is going to be. They also post videos of police brutality against unarmed black men, which of course has really fueled the Black Lives Matter movement into a worldwide phenomenon. There is a drawback, because technology also can be used to spread false information and undermine a dissent movement.

They say that history does not repeat itself. However, the recent developments in the United States after the death of George Floyd have revealed that racism and white supremacy is still a disease that affects America as a nation and society at its core. Do you think that the contemporary dissent and dissenters may effectively push America toward an unexpected direction to eradicate white supremacy and racial discrimination?

In 1967, when I was in university, I saw Stokely Carmichael give a speech. One of the white students asked him, after his talk on Black Power, what role there was for whites in the Black Power Movement. I loved Carmichael’s response. He said:

Don’t come into our neighborhoods to try to help us. That’s patronizing. Instead, what you can do is go into white neighborhoods and civilize the whites!

Is there any advice do you feel you can give to students and future historians who, like me, are trying to find their way in today’s world?

Don’t try to relive or emulate past movements and victories. Just be a part of your own time. And be a part of the solution, not part of the problem.