Carnival of Rome and Commedia dell’Arte: A Musicological Enquiry

The ongoing celebration for the Carnival in Rome have an ancient tradition which began with the pagan Saturnalia, and found its most typical modern characterisation in the XVI and XVII century Commedia dell’Arte. Although the latter was composed of several forms of art, its prominent musical practices and repertoires have been traditionally dismissed. Until now.

Celebrations for the Carnival of Rome

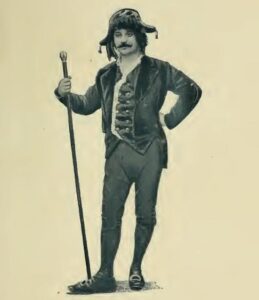

The Carnival in Rome has a very ancient tradition and is celebrated in that period of the year which comes before Lent. It is the feast of people, where all the rules of daily life are temporarily paused and make room for fantasy. For the event, Rome offers an extraordinary set of shows, over a crazy week dominated by masks, parades, allegory and tons of sweets. Although its celebrations acquire different features in any given city, Carnival has a general common semblance, for it grows out of certain pagan festivities including Ancient Rome Saturnalia, in which slaves were exceptionally promoted to the status of nobility. Carnival, in fact, is characterised by masks, by playing the role of someone different from what we really are, and by overthrowing the ordinary social order. The celebrations of the 2023 Carnival of Rome take place from February 16 to February 21, namely from “fat” Thursday to “fat” Tuesday, though in many other places they start on February 12. Take notes of these dates and enjoy a tour of Rome and of the several surprises it proffers in this period, next to its usual endless attractions! Streets and squares provide a great offer of entertainments, not to mention theatres and museums. Between Piazza Navona and Via del Corso you will meet the Romans in their traditional masks. Rugantino, above all, a character representing the romantic bull from Trastevere in his red neck foulard and old shorts, who ends up being decapitated due to his love for Rosetta. Next, Meo Patacca, Cassandrino, and many other characters belonging to the historical tradition of the Commedia dell’Arte who survived until today.

The Commedia dell’Arte

The Commedia dell’Arte is an Italian genre of comic entertainment which spread in centuries XVI and XVII, played by a company of actors who were apt to improvise their show just upon a generic plot. They were street artists who used to wear typical masks and colorful customs. The performers were musicians and the music was an essential component of such shows. Song, dance, musical accompaniment were inherited from Andrea Calmo and Ruzante’s comedies with their use of contemporary chansons and madrigals. There was a double layer of spirit in the Commedia dell’Arte: a first one, more vernacular, popular and dialectal obtained with the use of chansons, villotes, giustinanes, villanetes and of popular instruments such as the chitarrino, the colascione and the Spanish guitar; a second one, more “high” and literate, representing people who are in love (thanks to the exceptional presence of some women within the companies), realised through noble songs, madrigals, arias, accompanied by a liuto or a tiorba and reflecting the style of the cultural aristocratic world. The musical repertoire was usually unwritten, since the actors mostly used musical pieces and arias well known to the public and with a harmonic and metrical scheme, on which they could improvise new verses. Professor Anne MacNeil, Fellow of the American Academy in Rome, in her book Music and women of the Commedia dell’Arte. In the Late Sixteenth Century gave a fundamental contribution to the history of Italian music and theatre and their relationships to culture and politics in the period around 1600. She focused on the representation of women on stage and on the role of music-making in their craft and emphasized the role of the Commedia dell’Arte as a prologue of the opera in its gestational period. Nino Pirrotta as well, in his essay Commedia dell’arte and Opera, highlighting the linkage between the Commedia and the opera, reminded us that the definition of Commedia dell’Arte is just a modern one, given by scholars in order to underline that the performers were “professionals”, as the ancient Italian word “arte” had profession as a second meaning.

A Historiographical Gap

We did not inherit many fragments and documents belonging to the visual and musical parts of the Commedia dell’Arte, that were rather crucial and dominant within such performances. Due to the improvisational skills of the performers and to the common use of famous repertoires, we do not have detailed plots and sure musical pieces which used to be played in each performance. Even dance is a problem for early modern cultural historians, because though it was central to many people’s lives, from peasants to royals, seventeenth-century Europeans lacked a standard notation for choreography. If the Commedia was a literary product with occasional song and dance, the musicologist’s task would be limited to producing some necessary correctives. This has been done to some extent, although critical editions are few and far between. The Commedia, however, was not what most literary historians make it appear. By virtue of its origins it was, in the first place, dance and music and, by virtue of its history, in the second place spectacular entertainment. Only in the third place was it literature, whereby music always maintained a certain degree of preponderance over spoken parts. In other words, the trimming of the cake is of a literary nature, while the cake itself is dance and dance music. It would be of great interest to investigate the sources that we still have, illuminating the vanished aspects of these remarkable form of arts. When we speak of theatre products (which do not have the name of “opera”) of the Modern Era, we rarely mention the musical side of those. If we carefully end up in taking them into account, we rarely consider them as an essential part of the whole, but just as side random aspects. The limitative approach we adopt in that respect may mirror the current supremacy of other forms of art upon music, and is the consequence of a certain decline of music within our social perception of arts and knowledge. Dependent upon this reality, modern scholars have treated the comic plays at issue chiefly as texts to be interpreted from an exclusively literary perspective, while missing even complements of visual spectacle. Ben Jonson was the British poet deemed to be the main author of Masque, a court show which spread within Jacobinean England right after the Commedia dell’Arte arose in Italy, and which seems to have been directly inspired by the latter. His insights about the lasting role of written musical and literary documents once brought him to observe that the glorious visual, aural, and kinetic aspects of a masque were a kin to the mortal body — that is, “momentarie” and prone to being “utterly for-gotten” — whereas the poet’s voice, in the form of a preservable text, was comparable to the immortal soul.

On the Track of Music Tracks

For those who may be interested in a further investigation on the musical roots of the Commedia dell’Arte, the Biblioteca and Museo Teatrale Siae in Rome are an excellent source for theatre music: they provide important documents and objects such as letters belonging to some Italian comics from XVII century, paintings, stamps, small statues, costumes and masks of the most famous characters of the Commedia. The Burcardo Palace in Rome, in addition, is full of several documents telling the history of theatre from XVI century to date. The Bibliomediateca of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome is a huge archive of manuscripts, scores, collections, documents, audios, videos, photos. It is well equipped with computers which allow to consult on line catalogues, to listen and to watch digital documents, beside traditional reading spots and spaces dedicated to the study of manuscripts and ancient editions. For those who want to focus rather on the practice of the music performance of that time, instead, the Museum of Musical Instruments of Rome exposes an impressive collection of instruments belonging to the last two millennia, around three thousand items, eight hundreds of those exposed, coming from several areas of the world. The collection also includes many items used in the Commedia, such as liuto attiorbato, tiorbino, and arciliuto. Next to modern masks, parties, fried sweets, and clowns, save some time for you and your family to explore un unspoken repertoire of historical culture which bore the seeds of the current notion of Italian Carnival!

Feature Image: Fiodor Bronnykov, Roma. Carnevale a piazza del Popolo, 1860 – CC BY 2.0