Virginia Woolf: Bloomsbury’s Political Writer, Woman, Outsider

Virginia Woolf is one of the best known writers of British and World Literature. The Museo Nazionale Romano organised a documentary exhibition, still in progress, celebrating the spirit which spread within Bloomsbury, where Virginia proffered her contribution to new ideas which changed the Victorian mentality and the strong patriarchal flavour the 20th century was still imbued with.

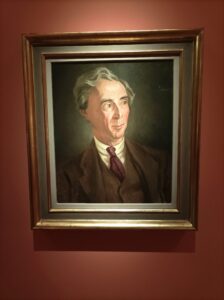

Virginia Woolf e Bloomsbury. Inventing Life is the first Italian exhibition dedicated to Bloomsbury and to its revolutionary ideals, on from October 26, 2022 to February 12, 2023 at Museo Nazionale Romano – Palazzo Altemps. The curator is Woolf’s expert Nadia Fusini who decided, in collaboration with writer and performance artist Luca Scarlini, to deploy the tale of Bloomsbury’s characters along the five rooms of astounding Palazzo Altemps. Many key-figures, including Leonard Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey and, of course, Virginia Woolf are portrayed in a sort of diary made of books, words, paintings, and objects belonging to such young intellectuals.

Virginia Woolf’s Life

Virginia Woolf was born in London on the 25th of January 1882. She was the third of four children and grew up in a very intellectual home, where reading and writing were natural and routinary activities. A complicated household and many personal tragedies contributed to the episodes of madness that burdened her life and work: Virginia lost her mother at age thirteen, her older step-sister Stella at fifteen, and her father when she was twenty two. She also had considerable experience with the disadvantages suffered by women at that time. While her brother went up to Cambridge as a matter of course, she remained at home with her sisters to study, read, think, paint, so long as these activities were the main ones the heavy social conventions demanded for women of their class. After the death of her father in 1904, the four siblings moved to the Bloomsbury district of London, where their household bore the early seeds of what would later become known in literature as the Bloomsbury Group. It was within this circle that she got in touch with the many intellectuals I mentioned, including Leonard Woolf whom she will marry. After another of several breakdowns that tormented her during her life course, she committed suicide by drawing herself into river Ouse in Sussex, in 1941.

Her Political Attitude

Virginia Woolf is often seen as a political writer, although not a successful or influential one, and almost never as a theorist with a comprehensive grasp of the society we live in. For the most part, the political insights of her books go unnoticed and essay upon essay focuses chiefly on the aesthetic and stylistic qualities of her art. In reality, Woolf developed a political conscience of her own, which she tends to show in many of her works, especially the last ones of her copious production. Woolf’s political concerns are primarily, but not solely, related to the power relations affecting the life of women in society, and to the traits of domination and tyranny that citizens experience within and beyond the borders of their country. Woolf attempts to denounce the suffocating structures of patriarchy within the British society, revealing a certain disdain of dictatorship both in its public appearance and in its domestic and hidden form. “Society” is to Woolf a word which acquires different meaning in relation to one’s sex: for women, «the very word “society” sets tolling in memory the dismal bells of a harsh music: shall not, shall not, shall not. You shall not learn; you shall not earn; you shall not own; you shall not – such was the society relationship of brother to sister for many centuries» (Three Guineas). While Woolf believed to be possible that one day a different society would exist, nonetheless it was clear to her how distant the day was: in the meantime, it was necessary for women to work on their own in the attempt to impress the necessary changes, defending their own culture and intellectual liberty.

An underrated fighter

Virginia’s husband wrote a remarkable autobiography, in which many pages are dedicated to tracing the course of Virginia’s work and illnesses. Leonard Woolf described that she had flights of inspiration during the course of their conversations, when he felt she suddenly «left the ground» and «gave some fantastic, amusing, entrancing, dreamlike, almost lyrical description of an event, a place, or a person […] The ordinary mental process stopped, and in their place the waters of creativeness and imaginations welled up and, almost undirected, carried her and her listeners into another world» (Virginia Woolf: A Biography by Quentin Bell, 1974). In addition to a description of her peculiar mind and personality, Leonard Woolf wrote that Virginia was «the least political animal that has lived since Aristotle invented the definition» and such a view was shared within Bloomsbury. Quentin Bell, Woolf’s nephew, labelled the fifty-two years Virginia as not really interested in politics. Academic Herbert Marder focused mostly on her art as a novelist and concluded that as a political writer Woolf was a failure: when she ceased to privilege arts in favour of politics, she became merely an unsuccessful propagandist. Feminist literary critic Elaine Showalter saw Three Guineas (1938) as representing «political naiveté» and «isolation from female mainstream», characterized by «empty sloganeering and cliché» and «stylistic tricks» which become «irritating and hysterical». In calling Virginia «the least political animal since Aristotle invented the definition», Leonard Woolf demonstrates superficiality in describing the real political attitude of his wife: stuck on her refusing agency within any political party, he does not show to grasp her peculiar attentiveness toward social patterns of power and domination, which she admittedly and harshly rejects. Undoubtedly Woolf herself was responsible for this view on her work: she dismissed conventional party politics and politicians as boresome. Yet, this mirrors neither apathy, unconcern, nor in fact bore, but just an intense revulsion against the world of politics as usual, a refusal of the conviction that such realm deserves our attention and energies. This was a position Woolf later adopted as a deliberate policy. She wrote in A Room of One’s Own (1929):

Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of men at twice its natural size» and continued: «Without that power […] [t]he glories of all our wars would be unknown […] The Czar and the Kaiser would never have worn their crowns or lost them». She claimed that if a woman «begins to tell the truth, the figure in the looking glass shrinks […] How is he to go on giving judgement, civilising natives, making laws, writing books, dressing up and speechifying at banquets, unless he can see himself at breakfast and at dinner at least twice the size he really is?».

A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas

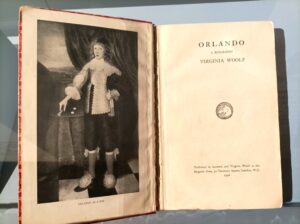

Three Guineas, together with A Room of One’s Own, represents Virginia Woolf’s major political work. They are both, quite explicitly, feminist polemics. The focus of A Room of One’s Own, like in her life as in her writings, was on the private sphere of women’s roles and the relations between the sexes. The book is filled with examples of the ridicule and contempt many men unwittingly show toward women, and of the humiliations women are subjected to in the daily life simply because they are women. To Woolf, a woman has two requirements for creativity in any endeavour, money, and a room of her own, “guineas and locks”. The money symbolizes economic independence, and the room the solitude and autonomy to turn off the world of family and community and to withdraw into the self to think and write. Both are simple, basic needs for any creative attempt by men or women, although Western societies have denied those to women far more often than to men.

Woolf has conceived Three Guineas as a sort of sequel of A Room of One’s Own. Three Guineas is considered a milestone of sexual difference feminism, an approach which allows her to develop a women’s politics of peace based upon women’s diversity from men, where womanhood can acquire the traits of pacifism. Woolf warns that if women want to contribute to the pacifist cause, they need to be educated with a college education insofar granted only to their male mates, and to access the world of professions, so leaving the domestic sphere. Only after granting them the equality they deserve in education and, in turn, in the professions, women can act as peace makers. Countering the social norms which impose domination over women, Woolf can be considered a politically engaged writer and an eminent figure of feminism.

Foto dell’autore

Foto in evidenza: Christiaan Tonnis ~ Virginia Woolf / Oil on canvas / 1998 licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license (CC BY-SA 2.0).